Nurturing Diplomats’ Ties to Family and Friends Back Home

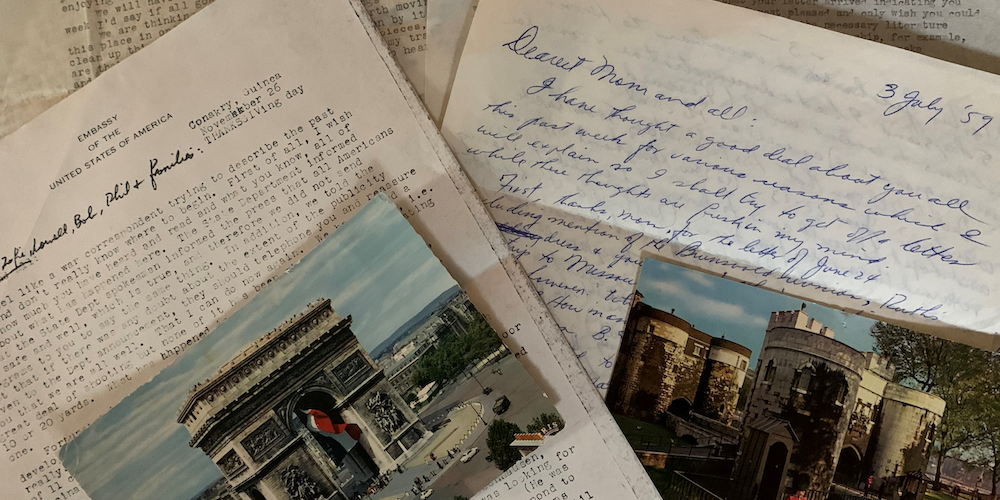

Long before email and social media, my parents wrote letters almost every week, not just on Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Diplomats spend their careers building and nurturing relationships with foreigners, sometimes at the expense of ties with family and friends back home. No matter how fascinating, satisfying or adrenaline-fueled, a diplomat’s peripatetic career comes with trade-offs that can take a personal toll. How many birthdays, reunions, weddings, graduations and funerals can one miss and remain an integral part of a family or circle of friends?

I grew up in the U.S. Foreign Service, and later joined it myself. For all the riveting and rich experiences during my career, there were also painful laments. When a dear cousin was dying, all I could do was talk with him from my first post halfway around the world. When a childhood friend’s husband suddenly passed away, it ate at me that I was far away, and not at her side. Not being there still haunts me decades later.

Taking stock of relationships I’ve been lucky to keep, one realization stands out: It was my parents, Donald and Patricia Norland, who instilled the value of tending to ties back home. That was what they did while in the Foreign Service, starting in the 1950s, well before today’s inexpensive means of communication we take for granted. Back then, ocean liners carried them to distant shores, letters took weeks, if not months, to reach home, and a phone call or packet of photos cost a small fortune. No matter. They found ways.

The groundwork for preserving family ties I cherish today was laid during childhood summer vacations with both of my parents’ families. Those gatherings allowed my siblings and me to get to know aunts, uncles and cousins, many of whom still enrich our lives today. Another linchpin were my father’s periodic postings in Washington, which made it possible to spend my formative years with family and friends. Whether in Washington, The Hague or Gaborone, the glue that bound my parents to loved ones came in the form of correspondence. Hand-written or typed, occasionally mimeographed so the text came out purple, their letters shortened the distance when no other contact was possible.

My parents wrote almost every week, often on Sundays, regardless of the pressures, crises or grand adventure du jour. Letters from home typically arrived once or twice a week in the diplomatic pouch. When Dad came home on a “pouch day,” it was exciting to rip open envelopes and small packages smothered in stamps. Dad was determined to educate his mother and siblings about diplomatic work — they had barely set foot off the family farm in Iowa. He tried to demystify diplomacy and make it relatable, like economics and agriculture, and to explain why engagement and cooperation with other countries served everyone’s interest. In turn, he hankered for their news. How was the harvest? What about the nieces and nephews, neighbors, friends and extended family?

To expand the circle of the recipients of his letters, in 1959, Dad began using carbon paper. He wrote that he wanted to “convey the sights, sounds, smells and sentiments of Abidjan,” the capital of Côte d’Ivoire, where the family lived at the time. “I have thought a good deal about you all this past week for reasons which I will explain, so I shall get off a letter while these thoughts are fresh in my mind,” he wrote in a letter to “Mom and all.” On another occasion, he reported that protesters against the arrest of a local labor leader marched “outside the balcony of the office toward the Legislative Assembly.” He mentioned talking to a reporter from the Des Moines Register and asked for any articles that might appear in the Iowa newspaper. He also explained that he had sent some photos “by surface, because airmail is so expensive ($5),” more than $50 today.

In a 1962 letter during his tour at the U.S. Mission to NATO, which was then headquartered in Paris, Dad commented on the “one inch” of snow that had fallen all winter in France, compared to the 30 inches in Iowa. Later, while at The Hague, he wrote about the defection of a diplomat from a communist country, who had sought refuge at the U.S. Embassy. “There is always a good deal of education to be had in an event like this, and it may be a long time before some of it becomes public knowledge,” he said. He also wrote about a speech to U.S. businessmen on “current Dutch attitudes towards world problems,” in which “I tried to reassure them that what they hear on TV or read in the press is not representative of the average Dutchman nor of the people who make Dutch foreign policy.”

In Mom’s letters home, she described experiences large and small, whether taking the kids to school or explaining the roots of a civil war. She wrote in an easy, accessible style and included vivid details. For example, she hosted about 200 guests on a sweaty July 4 in Abidjan with the help of “one small refrigerator.” When tailoring carbon-copy letters, she penned notes to each recipient in her curlicue handwriting.

Letters my parents sent after the 1970 amphibious attack on Conakry, the capital of Guinea, by Portuguese soldiers illustrate how important it was to stay connected, regardless of life at post. Dad wrote: “Thanksgiving Day. I feel like a war correspondent trying to describe the past five days and don’t really know where to begin. I wish I knew how much you have heard… The [State] Department informed the press all Americans were safe. We have heard a great deal of shooting but none within close range, i.e. 10 or 20 yards. What happened is another story, and a fascinating one.” He enclosed a five-page description I wrote, “which has the spontaneity and freshness that only a child of 11 can bring in the face or hearing of gunfire.”

I was in high school when we moved from Washington to Botswana and was miserable having to leave friends behind. My parents suggested sending cassette-tape recordings, so my friends could hear my voice, know how much I missed them and learn about another part of the world. And who didn’t relish a postcard with an eye-catching picture and a pithy paragraph signed by a loved one, topped off with an enchanting stamp? Instagram seems like a cheap imitation.

As diplomats, my spouse and I tried to emulate my parents’ stalwart correspondence habits. In the mid-1990s, when I joined the Foreign Service, email was still nascent and international phone calls were still very expensive. We’ve gained a lot with today’s easy and cheap communication tools, but we’ve also lost a lot. Writing letters takes thought and concentration. Email and texting mean that there are no letters to reread decades later and reminisce. The “in-the-moment” color and depth of letters stand the test of time.

My spouse and I are trying to return to letters, notecards and postcards. We are excited to have a new penpal, our 12-year-old great niece. When she is older, we will share her great-grandparents’ diplomatic adventures — thanks to their letters.

Patricia D. Norland is a former Foreign Service officer and the author of “The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance.”