Amid Chaos, Diplomats Aide Strange Power Transition

U.S. embassies, usually bustling with activity before a new administration, struggled to deal with the 2020 election aftermath.

By ROBIN HOLZHAUER and SOFIA OLMSTEAD | FEBRUARY 7, 2021

For American diplomats around the world, a U.S. transition of power is diplomacy gold — a time to showcase the best of democracy, celebrate stability, highlight civic responsibility and promote good governance. That gold underpins Washington’s credibility as it carries out its diplomacy globally. Credibility, in turn, has been the currency the U.S. Foreign Service has used for decades to maintain U.S. soft-power primacy, and to nudge other countries toward creating more open, just and inclusive societies.

The 2020-2021 transition has been a rare exception to the long tradition of American embassies bustling with activity as one U.S. administration prepared to take over from another. With public events already drastically curtailed by the Covid-19 pandemic, diplomats were in no rush to host press conferences or private briefings for foreign officials and other groups before Inauguration Day, because of the “chaos” in which the Trump-Biden transition was mired, said Steve Kashkett, a former career diplomat. If done right, the transition process provides for a “pretty good protocol,” added Kashkett, who was a Foreign Service officer for 35 years, until 2017. His last assignment was as deputy chief of mission in Prague.

Sheila Paskman, another former career diplomat, said that, in normal times, transition work at embassies and consulates usually begins with Election Day or Election Night parties — depending on the time zone — where the invited guests watch the results and projections. In 2020, most posts held no such events. While the pandemic was the apparent reason, many diplomats also privately cited extreme political tensions in the United States.

After it became clear that Joe Biden had won, diplomats were at a loss to explain to the world why Trump and his supporters were falsely claiming the election was “stolen” from him, and why his outgoing administration, including then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, was refusing to cooperate with Biden’s transition team. That refusal effectively blocked access by the incoming administration to diplomats both in Washington and abroad for weeks. Such communication is important, because it ensures that newly appointed officials are fully informed of any developments in other countries that may affect or be affected by upcoming U.S. decisions, policies and actions, said Magda Siekert, also a former longtime Foreign Service officer. Siekert was deputy chief of mission in Costa Rica during the transition from the George W. Bush to the Barack Obama administrations.

American diplomats’ exasperation reached fever pitch during and after the January 6 insurrection on Capitol Hill by a pro-Trump mob. Initially ordered by Pompeo not to post anything related to the attack on social media, hundreds of Foreign Service officers rebelled and later denounced the riot in official embassy statements, in an effort to reassure their host-countries that a peaceful transition of power would take place on January 20.

Another decades-long tradition calls for the outgoing president to ask for his ambassadors’ resignations shortly after a new leader is elected. Career diplomats usually remain in their positions, but political appointees step down on Inauguration Day at the latest. Trump didn’t ask for resignations until the day after the attack on Congress. That put some embassies in a precarious position, facing the prospect of political ambassadors refusing to leave.

On rare occasions, a new president would ask an incumbent political ambassador to stay on at least for a few months to provide for a smooth handover. That was the case in 2001, when then-President Bill Clinton’s envoy to China, Joseph Prueher, continued serving during the first four months of the Bush administration, recalled Paskman, the U.S. Embassy’s spokesperson at the time. Initially, Prueher planned to stay until April. But on the first day of the month, a Chinese fighter jet collided with a U.S. Navy reconnaissance plane, forcing it to land on China’s Hainan Island. With the 24-member American crew detained, Prueher remained in Beijing for another month to help then-Secretary of State Colin L. Powell resolve what became a major international incident. “We were in the middle of a crisis, and we had to have continuity,” said Paskman, who was later deputy chief of mission in Liberia.

Amid tensions in the U.S.-Russia relationship and unprecedented popular protests in the vast country in support of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, Biden asked Trump’s last ambassador, John Sullivan, to remain in Moscow. Navalny, who was the target of an assassination attempt in August, which he blames on President Vladimir Putin, returned to Russia last month after recovering in a German hospital. He was arrested upon arrival, and a court sentenced him to more than two years in prison last week. Biden called for his immediate release.

Despite each new administration’s attempts to put forward new initiatives and leave its stamp on foreign policy, few long-term relationships with other countries have undergone significant shifts in recent decades, under both Democratic and Republican administrations. Foreign leaders have generally known the fundamental U.S. position on their respective countries, as well as the interests, values and principles that form the bedrock of American foreign policy.

That all changed with Trump’s election in 2016, Kashkett said. Trump’s withdrawal from trade, nuclear and climate agreements, threatening to leave NATO and insulting some of the staunchest U.S. allies upended the international order and Washington’s global leadership role. “In Europe, there was deep apprehension about Trump’s admiration for Putin and the prospects that Trump would turn a blind eye to Russian aggression in Ukraine and elsewhere in Europe,” Kashkett said. “The Obama-Trump transition put U.S. diplomats all over the world in the awkward position of having to reassure foreign governments that Trump was not going to turn every aspect of U.S. foreign policy upside down.”

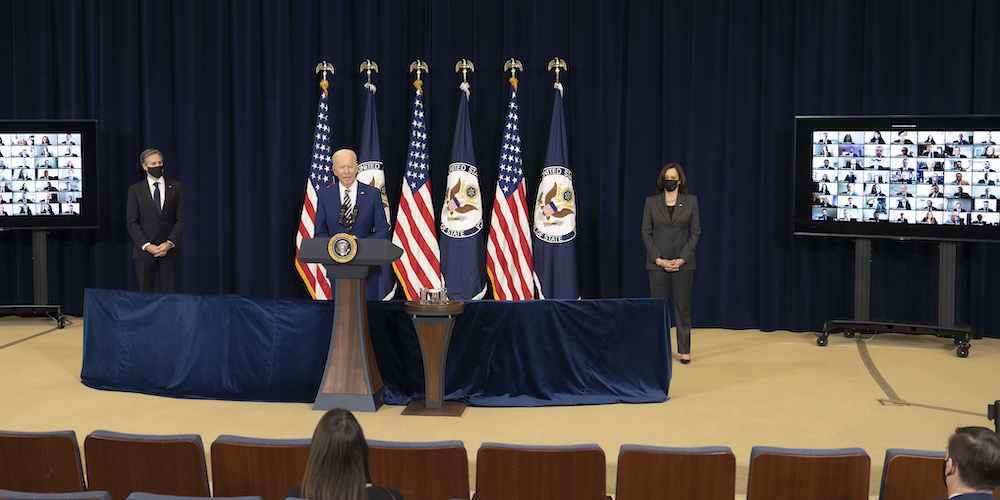

Career diplomats said they are always ready to spend many late nights, weekends and holidays to help prepare a new administration for both the routine demands of daily diplomacy and any urgent challenges that need to be addressed early on. They also want political appointees to understand what exactly the Foreign Service does, and to appreciate its sacrifices. That’s why a speech Biden delivered at the State Department last week was music to their ears.

“I promise you I’m going to have your back,” Biden told department employees. “You are the heart and soul of who we are as a country.”

Robin Holzhauer is the Diplomatic Diary’s senior editor. During more than 20 years as a Foreign Service officer, her postings included Russia, Kosovo, Venezuela, Lebanon and Gabon.

Sofia Olmstead, an intern at the Diplomatic Diary, is a student at American University’s School of International Service.