Foreign Service Promotion Process Falls Short of Diversity Goals, Audit Finds

Implementation of a new report’s recommendations is in doubt under the next administration.

By CHARLES RAY | DECEMBER 8, 2024

Every spring, members of the U.S. Foreign Service are required to submit performance evaluation reports, and every summer, dozens of panels review those reports and determine who deserves to be promoted to the next level in the bureaucratic hierarchy. Like the military, the Foreign Service has an up-or-out personnel system, in which every officer has a certain number of years to get promoted — failure to do so spells an end to the officer’s career. In addition to the State Department, the service includes representatives from the Departments of Commerce and Agriculture, as well as the U.S. Agency for International Development.

A new report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) last week criticized the State Department for failing to fully implement changes recommended in a 2021 study aimed at making the Foreign Service promotion process more fair, inclusive and effective. “State has not expanded the demographic criteria for selection boards to ensure they reflect the composition of the Foreign Service, including ethnicity and disability status, as suggested by a GAO leading practice on diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility,” the report said.

During my three-decade diplomatic career with the State Department, I served on several promotion boards — for both diplomats, also known as “generalists,” and “specialists,” such as accountants, security officers, technical experts and office managers. When I chaired a panel for specialists, I got into a lengthy argument with one of the board members over the promotability of a budget management specialist, who had volunteered for two consular assignments in the past five years. The board member in question, a personnel specialist, insisted that the employee shouldn’t get promoted, because he hadn’t spent enough time working in his budget specialty.

Each panel is responsible for evaluating hundreds of employees, and it’s a luxury to spend even a few minutes discussing an individual’s performance. But in this case, it took me more than an hour to persuade my colleagues that the budget officer’s consular work, which appeared to have been outstanding, should be taken into consideration and he should be promoted — only the personnel specialist couldn’t be convinced, but she was outvoted. Even though the State Department encouraged all Foreign Service members to take assignments outside of their specialty to broaden their skills and expertise, she had decided unilaterally that such experience should be ignored for promotion purposes.

This made me realize that the promotion system had serious flaws. Too much was left to personal interpretation or biases of those selected to sit on promotion boards, who themselves came from a variety of specialties, not just the one that was the subject of the panel. I was a generalist in the management career track, but I had only one tour in that track in 30 years, which didn’t prevent me from being promoted to the Senior Foreign Service and becoming an ambassador. Now, more than a decade after retiring, I find from the new GAO audit that a problem I thought had been remedied, when the State Department established the position of a chief diversity officer nearly four years ago, still persists.

“State made changes, such as introducing a scoring rubric for promotion panels to rate and provide feedback to candidates,” the GAO said. “However, it did not document its assessment of the usefulness of the leading practices.” In addition, the department “has generally followed but not fully documented its requirements for the composition of selection boards,” the report noted.

In the past, an employee’s immediate supervisor and a higher-ranking official could make explicit recommendations for promotion as part of their evaluations. That is no longer allowed. Superiors are now directed to clearly illustrate the extent to which the employee has demonstrated potential to perform successfully at the next level. Other changes included modified core promotion precepts to reflect the competencies most critical to each level, and a new precept was added to address how employees show inclusivity and respect in their relations with colleagues and others. Again, however, the GAO report concluded that State failed to document its assessment of the usefulness of these practices in achieving its reform goals.

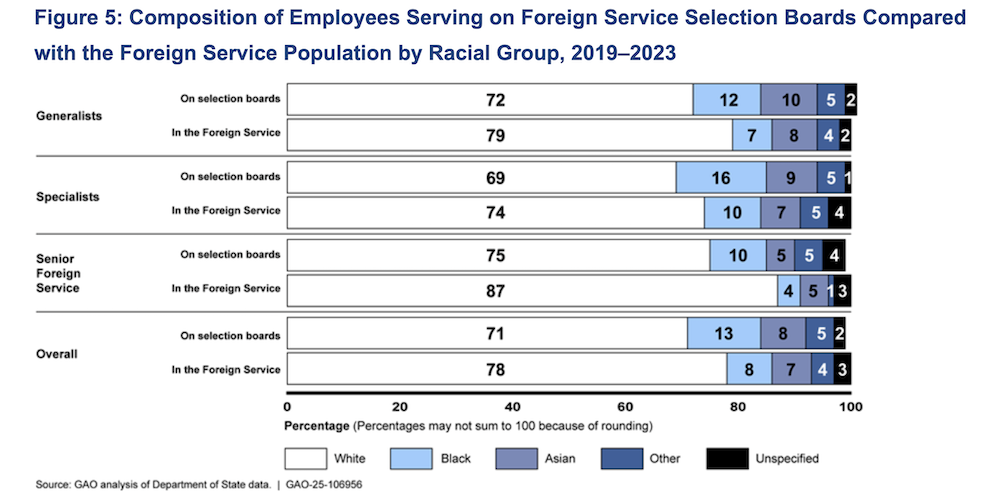

As anyone who has worked in a government bureaucracy knows, what’s written on paper isn’t always reflected in actions. Between 2019 and 2023, the percentage of women and historically disadvantaged racial groups on promotion boards was higher than their percentage in the Foreign Service overall, according to the GAO — 49 percent compared to 37 percent for women, and 27 percent versus 20 percent for racial minorities. But the numbers of ethnic minorities, such as Hispanics, and employees with disabilities were lower on promotion panels than in the workforce — 6 percent compared to 8 percent for the former, and 7 percent versus 9 percent for the latter. Personally, I don’t recall ever serving on a promotion board that included a member with a disability.

It’s not enough for the State Department to create a definition or benchmark and publish it in the Foreign Affairs Manual, its guide of rules and regulations. There has to be ongoing assessment of the effectiveness of the benchmarks and procedures, and documentation accessible to employees to help them understand the background and meaning of each rule. The GAO recommended the secretary of state ensure that is done going forward. The Foreign Service shouldn’t just represent — or look like — the population of the United States; it should represent the country and its interests effectively.

Although the State Department accepted the GAO’s recommendations, their implementation will be a challenge under the next administration, given its hostility toward diversity programs. The Foreign Service, like the U.S. military, is a nonpartisan institution whose members commit to carrying out the policies of the elected leadership, whether or not they agree with them. Abandoning State’s diversity efforts would have a negative impact on employee morale and the quality of our diplomatic efforts around the world.

Charles Ray is a former U.S. ambassador to Zimbabwe and Cambodia, deputy chief of mission in Sierra Leone and consul general in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. He spent 30 years in the Foreign Service and now teaches at WIDA.

The opinions and characterizations in this article are those of the author and don’t necessarily represent the views of the U.S. government, the Diplomatic Diary or WIDA.