More Americans Seem to Appreciate Diplomacy. Is That Enough?

The State Department has made some progress in public outreach, but it still needs a realistic and coherent long-term strategy.

By ROBIN HOLZHAUER | SEPTEMBER 11, 2022

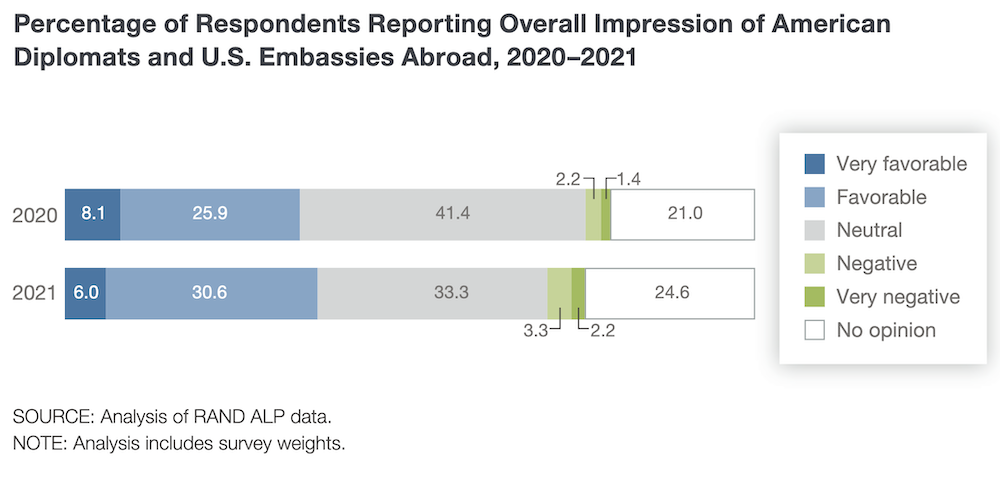

During the extraordinarily challenging days for U.S. diplomacy under the Trump administration, diplomats received barely noticed but hopeful news from a highly respected pollster. According to a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center, 73 percent of Americans said that “good diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace.” In addition, 68 percent said that the United States “should take the interests of allies into account, even if it means making compromises.” Another survey earlier this year by the RAND Corp. showed more than 65 percent thought that “diplomacy contributes to national security.”

Few Americans know what diplomats do, so any public opinion polling on diplomacy and the Foreign Service should be interpreted cautiously. In fact, in the RAND survey, less than half of the respondents said that “it was better for diplomats to lead efforts abroad than the military.” As generally positive as the two polls’ results were, they should not lessen the need for what the State Department has been struggling to accomplish for years: Explain to Americans what its diplomats do around the world, why it matters to the daily lives of all U.S. citizens, and why diplomacy should be better funded.

Although the department has made some progress, durable long-term success requires a realistic and coherent strategy, which it currently lacks.

Officials usually point to two main programs as examples of their outreach efforts. The first is run by the department’s recruitment office and stations 15 career Foreign Service officers, known as “diplomats in residence,” at universities across the United States. Their primary job is to help recruit new diplomats, not to educate large groups of Americans about the importance of diplomacy. The other program, “Hometown Diplomats,” encourages department employees to give talks to community and school groups when they go back home for personal reasons. However, there is little effort to recruit volunteers, few actually do it, and it lacks proper coordination and strategic use of their efforts.

Last year, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said he would make it a priority to send senior officials on regular trips around the country to engage with domestic audiences. So far, such travel has not been much more frequent than similar activities under previous administrations, and most of it has involved groups connected to or already interested in foreign affairs, so in a way, preaching to the choir. Again, there has been no apparent coordination or strategizing behind those efforts.

The State Department has a public liaison office, which says on its website that it “reaches tens of thousands” of Americans every year, but there are no examples or a list of past or future activities — only a form to request a speaker for events. In 2017, the department opened the National Museum of American Diplomacy at its headquarters, but it’s still under construction and not much can be seen yet. With creativity and innovation, it could become a must-see museum for visitors to Washington. It could also expand the department’s existing collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution to include partner exhibits that explain the role of diplomacy and diplomats in both American history and current events. Some of them could be traveling exhibitions.

Polling over the last two decades has made clear that most Americans think the federal government spends about 25 percent of its budget on international affairs, including foreign aid. The actual number is slightly more than 1 percent. For that misperception to be corrected — and for the budget to increase — it is essential for Americans to know that U.S. diplomats manage complex relationships with both allies and adversaries, negotiate trade and other agreements, assist U.S. companies in investing abroad, promote the United States as an educational and tourist destination, fight corruption, protect human rights and free speech, and help their fellow citizens in need abroad.

The American Foreign Service Association, the diplomats’ union, has worked hard in recent years to help educate Americans about the impact of diplomacy on their lives, as have several private organizations, including Associates of the American Foreign Service Worldwide, DACOR and the American Academy of Diplomacy. Podcasts such as “American Diplomat” and “The General & the Ambassador” offer insights into the Foreign Service, but they receive limited attention. On the rare occasions diplomats are depicted in movies and on TV, they usually don’t come off very well.

The State Department needs to design a well-thought-out and innovative strategy to explain the daily work of diplomacy in clear, relatable and impactful terms to the American public. The beginning of such an effort could include requiring certain forms of domestic outreach for officers to be promoted to the senior Foreign Service. The department could coordinate closely with outside organizations and even support them. It could also study carefully and try to emulate the Pentagon’s wildly successful program to consult on thousands of Hollywood productions.

When I told family and friends that I had joined the State Department more than 20 years ago, they often responded, “Really, in what state?” When I tried to clarify that I had joined the Foreign Service, some said they didn’t know that Americans were allowed in the French Foreign Legion. Many of my former colleagues still encounter the same reactions today. It’s high time that changed.

Robin Holzhauer is the Diplomatic Diary’s senior editor. During more than 20 years as a Foreign Service officer, her postings included Russia, Kosovo, Venezuela, Lebanon and Gabon.