Why It Takes So Long to Appoint U.S. Ambassadors

The answer lies in a mix of legal requirements, a cumbersome government bureaucracy and, not surprisingly, politics.

By NICHOLAS KRALEV and LOUIS SAVOIA | JUNE 13, 2021

Members of Congress have complained for years that both Republican and Democratic administrations take too long to nominate U.S. ambassadors. The administrations, in turn, have often rebuked the Senate for delaying many nominees’ confirmation. Foreign leaders have made their displeasure known as well. In a recent thinly veiled criticism, former Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović was perplexed by the absence of an American ambassador at NATO, which tomorrow opens a highly anticipated summit, the first for President Biden.

Given that it takes more than a year on average from the time candidates are selected to their swearing in as ambassadors, one would think that foreign officials are used to the slow-moving process. But they seem surprised with every new administration, and there is little Washington can do to persuade them that the delay in sending an envoy should not be seen as an affront to their country.

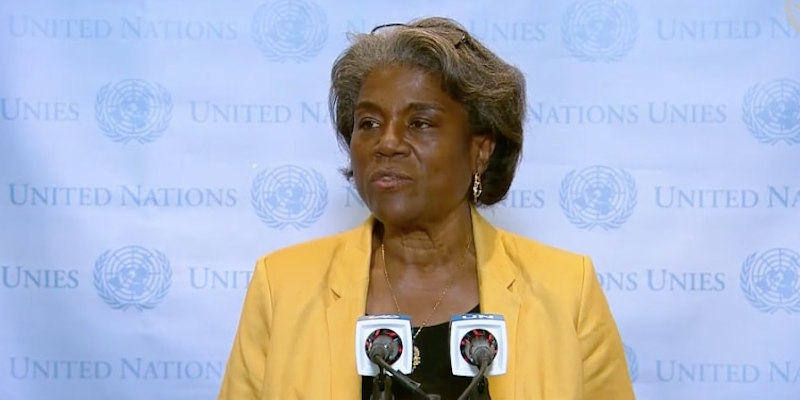

Almost five months into Biden’s tenure, he has nominated 11 ambassadors. The only one confirmed by the Senate is his envoy to the United Nations in New York, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, a retired career diplomat who took office in February. Another nomination, for U.S. representative to the world body for management and reform, which carries an ambassadorial rank, was announced in April. The other nine nominees are career Foreign Service officers, who would go to developing countries such as Algeria, Angola and Senegal. In contrast, non-career appointees, who have won about one-third of ambassadorships for decades, prefer Western Europe and rich or highly important countries elsewhere, as well as international organizations like NATO and the European Union. They typically have a business or political background.

The rotations of career ambassadors are usually not affected by a change of administrations. The nine career Biden nominees will fill vacancies not related to the transfer of power in Washington. Currently, 89 of 187 total ambassadorial positions are without a nominee.

So why does it take so long for ambassadorial nominations to be announced, and then for nominees to be confirmed? The answer lies in a mix of legal requirements, a cumbersome government bureaucracy and, not surprisingly, politics.

The White House usually starts the process by compiling two lists, several former ambassadors said. The first is a list of potential political appointees — historically, most names on it have belonged to campaign donors and fundraisers, known as bundlers, who helped the president’s election, as well as others with political connections. The other list is of countries to which the White House wants to send non-career ambassadors. Ideally, there would be a “specific reason” for a candidate to be “matched to a particular country,” said Cindy Courville, a former ambassador to the African Union and special assistant to then-President George W. Bush.

In reality, however, very few political appointees have country or regional expertise, and almost none speaks the host-country’s language. Courville was among the few foreign policy experts to become a political ambassador. A retired civil servant and former university professor, she was the senior director for African affairs at the National Security Council when she was offered the post at the African Union in 2006. “I hadn’t envisioned that I would be asked to serve,” she recalled.

As part of the selection process, the White House senior director for legislative affairs consults with the State Department to make sure there are no red flags in a candidate’s past that could jeopardize Senate confirmation, Courville said. “The more upfront and transparent an individual is, the better,” she said. If red flags are found, the name can be withdrawn. Even if the White House produces a list of potential nominees quickly, the formal vetting can take months, Courville said. A “coalition of agencies” conducts various financial and security investigations, including the Office of Personnel Management, the FBI and the State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security, she noted. Candidates must disclose financial holdings and liabilities, work and travel history, as well as provide the names of friends and colleagues to be interviewed. If a nominee owns a large company, it takes even longer to figure out what to do with those assets, Courville added.

Career nominees have usually undergone such investigations long before they are nominated. They “have to submit financial disclosure forms on an annual basis,” said Gordon Gray, a former ambassador to Tunisia who spent 33 years in the Foreign Service. Still, that doesn’t mean that the process for them is much shorter. First, the State Department has to wait for the White House to decide which countries will be available to professional diplomats. Then senior Foreign Service officers make their interest in particular positions known, and the ensuing competition can take months. The respective regional bureau at the department identifies its top candidates for each opening, taking into account “career achievements, geographic and subject-matter expertise, leadership and managerial experience,” said Kathleen Doherty, a former Foreign Service officer who was ambassador to Cyprus.

Matthew Bryza, another former Foreign Service officer who was ambassador to Azerbaijan, said that the competition is fierce. “It gets down to a process of identifying reasons to exclude somebody, because everybody is so qualified,” he said. There is no guarantee that the so-called Deputies Committee, chaired by the deputy secretary of state, will end up recommending any of the regional bureau’s top choices to the secretary of state. Nor is it certain that the White House will approve the secretary’s eventual career candidate — it could even take away a post that was supposed to go to a career nominee, because a certain political candidate wants the country in question.

Once the White House has an official candidate, it informs the host-country of the selection and seeks agrément, or acceptance. Rarely denied, it’s usually the final step before the official announcement of the nomination.

Both career and political nominees could wait for months to get a hearing in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and even longer for a vote in the full Senate. Earl Anthony Wayne, a former career ambassador to Argentina and Mexico, said that senators may delay a confirmation for leverage with the administration in office, often over policy matters not related to the nominee. Courville agreed. “Because I was coming from the White House, I was perceived as being close to the president,” she said. “I waited nine months for a hearing. They were looking to leverage something else, and I was caught in the middle.” Gray said he got lucky that he was “batched” in a group with a high-priority political nominee and was confirmed relatively quickly. In Wayne’s case, one of his confirmations was delayed over an unrelated matter, but the other one was speedy, he said.

Almost five months into the Biden administration may seem a long time, but no former ambassador is surprised by the still vacant positions. Doherty said that, from the time she expressed interest in the ambassadorship to Cyprus to her arrival in the country, “the process took about 18 months, and that was considered relatively fast.”

“None of this happens quickly,” Courville said.

Nicholas Kralev, the executive director of the Washington International Diplomatic Academy, is the author of “America’s Other Army: The U.S. Foreign Service and 21st-Century Diplomacy.”

Louis Savoia is an intern at the Diplomatic Diary.