The State Department’s Million-Dollar Mistake

The money was spent to establish a second residence for Trump’s ambassador to South Africa. Under Biden, that decision was rescinded.

By NICHOLAS KRALEV and ROBIN HOLZHAUER | FEBRUARY 28, 2021

The State Department has reversed its months-old decision to establish a second ambassadorial residence in South Africa, effectively admitting a mistake that cost American taxpayers as much as $1 million. Despite extensive renovations and new furniture purchases, the residence was never used for its intended purpose and has now been returned to the U.S. consul general in Cape Town, from whom it was taken in the first place, department officials said.

The building is again “a consul-general residence,” a spokesperson in Washington said. Diplomats welcomed the news but criticized as reckless and wasteful the initial decision, first reported by the Diplomatic Diary, to give in to a demand by a political ambassador, who wanted another house nearly 1,000 miles from the embassy in the capital Pretoria. “All’s well that ends well, but all that money and stress” were completely unnecessary, said one diplomat, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution.

The former ambassador, Lana Marks, who served during the last year of the Trump administration, appears to have finally vacated the primary residence in Pretoria, weeks after she left office upon President Biden’s inauguration, sources said. Officials wouldn’t confirm her departure. In an extraordinary move, the State Department allowed Marks to remain in the residence and keep her diplomatic status, even though she no longer worked for the U.S. government. Department officials said she was recovering from Covid-19 and immediate travel wasn’t a good idea.

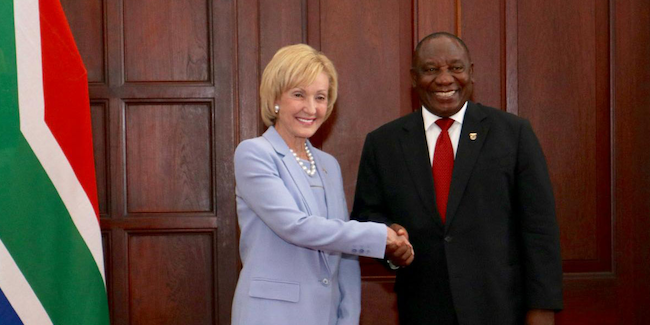

Lana Marks presented her credentials as U.S. ambassador to South Africa to President Cyril Ramaphosa on Jan. 28, 2020. Photo by U.S. Mission South Africa.

A South Africa-born handbag designer and paying member of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club in Florida, Marks, 67, had no previous experience in diplomacy. Just months after arriving in Pretoria at the end of 2019, she strongarmed the State Department into evicting the consul general in Cape Town, Virginia Blaser, and her family from her official residence and turning it into a second ambassadorial residence, so Marks could use it during visits to the city, diplomats said. Cape Town is considered much nicer than the capital, and she wanted to spend more time there but avoid hotels, they added.

Marks demanded extensive renovations and new furniture, the diplomats said. The State Department wouldn’t reveal the amount of these and other expenditures associated with the house’s conversion, but sources involved in the process estimated the figure at around $1 million. More than a month after the original Diplomatic Diary story’s publication, which made significant waves in the South African media, no department official has disputed that figure. “It was extremely poor use of taxpayer money, and a very poignant example of excess,” one diplomat said at the time.

Marks received support for her push to take over the building in Cape Town from the State Department’s Bureau of Overseas Building Operations, officials said. At least one official said that she all but threatened the bureau’s director at the time, Addison Davis, another Trump political appointee, with badmouthing him to the president, claiming a close relationship with him. In November, the bureau put out a “fact sheet” announcing the designation of the house as a second ambassadorial residence. The ambassador has authority over the entire U.S. diplomatic mission in South Africa, including the embassy and the consulates in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Durban.

Decades ago, the United States established an ambassadorial residence in Cape Town — the official reason was that the city was the seat of the South African Parliament, and foreign diplomats needed to observe its sessions. With instant communication and easy travel, however, the practice of U.S. ambassadors living in the city for months mostly ended about 20 years ago, according to diplomats who served there around that time.

In 2011, the State Department determined that the second U.S. ambassadorial residence, underused and too expensive to maintain, was no longer needed — in the preceding year, the ambassador had stayed there for a total of less than two weeks. So the house became the residence of the consul general, and since then ambassadors have stayed in hotels when they visited, usually for just a few days at a time.

“There was no legitimate reason for the ambassador to be in Cape Town for extended periods,” one official said of Marks. “The government of South Africa has been planning to move Parliament to Pretoria, and during Covid-19, all sessions have been virtual.” Moreover, no session takes place between November and January, when Marks’ tenure ended, the official noted, adding that she apparently believed Trump would win reelection, and she would stay in her post much longer.

Last week, State Department officials said the Cape Town residence won’t be used by the ambassador in the future. Blaser completed her tour in the fall, but her successor as consul general, who has yet to arrive, will live in the house. Last spring, Blaser had been ordered to move out by the end of July, three months before her tour ended. It’s not clear what alternative housing, if any, the embassy found for the Blaser family. She couldn’t be reached for comment.

In spite of the $1 million expenditure, Marks never used the second residence. Her target move-in date was pushed back several times, ostensibly because she wasn’t satisfied with the renovations and the new furniture, diplomats said. In December, she made a brief visit to Cape Town — her last as ambassador — but stayed in a hotel, they added.

Soon after returning to Pretoria, Marks was hospitalized for Covid-19 and spent 10 days in intensive care, according to a statement she released after being discharged in early January. She asked the State Department to remain in the official residence for several more weeks after leaving office, citing her condition. Some diplomats questioned the department’s acquiescence — even if travel wasn’t an immediate option, she could have moved to a hotel, they said. Some of Marks’ former subordinates recalled that she played down the coronavirus’ seriousness for weeks last year, refusing to wear a face mask and discouraging embassy employees from doing so.

Marks’ case is just the latest example of how ambassadors owing their positions entirely to political connections can abuse their power with impunity. She is all but certain to face no accountability for her actions. The only meaningful punishment political ambassadors can suffer while in office is dismissal. But once they leave government service, the system provides for no punishment or other consequences.

Biden has yet to nominate a new ambassador to South Africa. One of the names floating in Washington circles is that of Jeff Flake, a former Republican U.S. senator from Arizona, who was a Mormon missionary in South Africa and Zimbabwe in his youth. Flake has acknowledged that he has been in touch with the White House regarding a possible ambassadorship but has not named a specific country. Calls against sending him to Pretoria have already started, citing his support for South Africa’s apartheid government in 1987, when he was a state senator in Utah.

Nicholas Kralev, the executive director of the Washington International Diplomatic Academy, is the author of “America’s Other Army: The U.S. Foreign Service and 21st-Century Diplomacy.” He covered the State Department for a decade as a Washington Times and Financial Times correspondent.

Robin Holzhauer is the Diplomatic Diary’s senior editor. During more than 20 years as a Foreign Service officer, her postings included Russia, Kosovo, Venezuela, Lebanon and Gabon.