WIDA Instructor William Burns Named CIA Director

The first diplomat to lead the agency, his tenure is an opportunity to improve the strained relationship between diplomacy and intelligence.

By NICHOLAS KRALEV | JANUARY 17, 2021

In the minds of people around the world, diplomacy — to the extent they ever think of it — is a cover for spying. That often irks real diplomats, even though they understand the value of intelligence and appreciate the sacrifices a spy’s job demands. After all, they are all part of the same embassy communities. Their relationship has long been complicated. Intelligence officers often view diplomats as risk-averse bureaucrats trying to tame their daring operations. Foreign Service officers accuse spies of blowing up fragile relations with other countries and derailing delicate but crucial policies. Although the two sides know a lot about each other, their cultures and mentalities are very different.

So there is at least some irony in President-elect Joe Biden’s decision to put a career diplomat in charge of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for the first time in its history. The nominee, William Burns, a former deputy secretary of state who was also ambassador to Russia and Jordan, has taught at WIDA for the last three years. Since he was a front-runner to be secretary of state, even we were surprised by his actual new job.

Writing in The Atlantic in 2013, I called Burns “the White House’s secret diplomatic weapon.” His careful but masterful handling of the bureaucracy and his lack of desire to grab the limelight were as important to his success as his diplomatic skills, I wrote. Both Democratic and Republican secretaries of state have sung his praises. During the George W. Bush administration, Colin Powell appointed Burns as assistant secretary for Near East affairs, and Condoleezza Rice promoted him to undersecretary for political affairs, the third-ranking position at the State Department. In the Obama administration, Hillary Clinton elevated him to deputy secretary, and John Kerry kept him in that post.

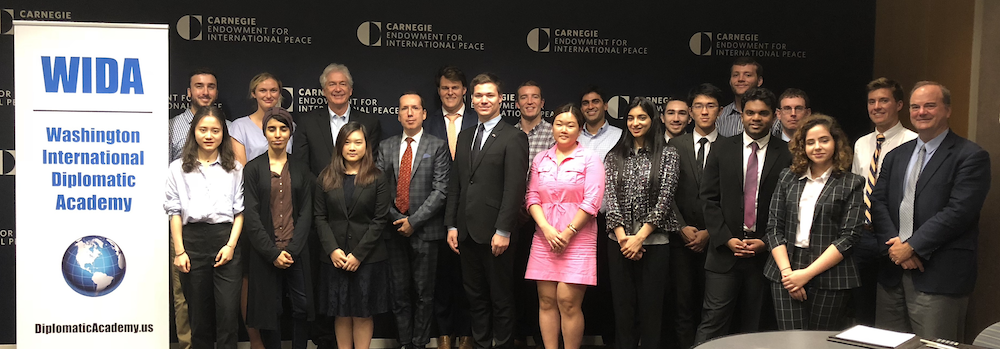

Ambassador William J. Burns with WIDA students in 2019.

“He immediately lived up to his stellar reputation as a seasoned diplomat, and I have valued his insight and judgment every day,” Clinton told me in 2009. “He personifies the very best of our Foreign Service and is a model of dedication to our country.” Kerry called Burns “the gold standard for quiet, head-down, get-it-done diplomacy.”

“He is smart and savvy, and he understands not just where policy should move, but how to navigate the distance between Washington and capitals around the world. I worked with Bill really closely from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and I’m even more privileged to work with him now every single day. He has an innate knack for issues and relationships that’s unsurpassed,” Kerry told me in 2013. “Whenever we are hunting for talent, I tell people I want to find the next Bill Burns. He embodies exactly the combination of capable and agile thinker and doer that the career Foreign Service was envisioned to produce.”

James A. Baker, secretary of state in the George H.W. Bush administration, called Burns a “top-notch public servant” who “speaks truth to power in an understated way.” He is “not ideological, calls it like he sees it, and everybody has confidence in him,” Baker told me in 2004. “I don’t know anyone who thinks ill of him, and if you look at the results of his work, you will know why.” Richard Armitage, who was deputy secretary of state in the George W. Bush administration, said, “What makes Bill so special is that he is calm, unflappable, informed, with an absolute steel core. He is a man of principle who will not bow to expediency.”

Burns had the most astonishingly meteoric climb up the Foreign Service ladder of any officer I know. In a highly unique career, he made it into the Senior Foreign Service in just 10 years, less than half the time it takes the average officer who eventually gets promoted to the senior ranks — many don’t make it there at all.

Having joined the service in 1982, Burns’ first big break came during his third tour, as a junior aide in the Middle East office of the National Security Council in the Reagan White House. A couple of months into the tour, the office was shaken by a huge scandal that became known as “Iran-Contra.” A more senior staff member on detail from the military, Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, had devised a plan to sell weapons to Iran and use the money to fund illegally Nicaraguan anti-communist rebels known as Contras. The plan had been approved by Reagan’s national security adviser at the time, John Poindexter — no evidence has been found suggesting that the president himself authorized it — and other staff members had helped to implement it.

Within months, most of the NSC staff, including Poindexter, were replaced. Burns, who had no idea about Iran-Contra until it was publicly exposed, was one of the few to survive. “I was so junior, I don’t think anybody took any notice,” he said in an interview for my book “America’s Other Army.” At the end of 1987, Colin Powell became national security adviser, and the following year he put Burns in charge of the Middle East office. “I thought more senior people should do it, but Powell said, ‘I wouldn’t ask you if I didn’t think you could do it.’ It was dumb luck. I was 32,” Burns recalled. “In the Foreign Service, how well you do depends a lot on who you work for and what you work on. I was really lucky, but I know people who weren’t so lucky.”

Having bosses who entrusted Burns with significant responsibilities was critical for his speedy rise. But there is another factor when it comes to having a long and fulfilling career, he noted. “To become a good professional, you have to do it right, so you are well prepared for your next job,” he said. “If you want to build a good foundation, not only does that create more career options, but it’s also going to be more interesting. So develop a foothold in more than one region.” Burns did just that. At the end of his first decade in the service, he decided to add Russia to his Middle East expertise. While he was learning Russian at the Foreign Service Institute in preparation for his assignment as political counselor in Moscow, Thomas Pickering, the ambassador there at the time, asked Burns to cut his studies short and come to Russia earlier to be deputy chief of mission. As much as Burns respected and admired Pickering, he declined the offer in favor of the original plan. “I wasn’t ready,” he said. “I wanted to do it right.” A decade later, he returned to Moscow as ambassador.

Despite Burns’ success, however, identifying promising young Foreign Service officers and nurturing them to become strong leaders and top-notch diplomats has been a weakness of the service. Burns urged senior officers to “pay more attention to the mid-levels” in particular, where assignments should be taken more seriously, because those are the formative years for most diplomats. “We need to make a conscious effort to put the right people in the right places,” he said. Such an approach would be useful in the senior levels, too, Burns added. For example, when selecting a career ambassador to a certain country, “we ask, ‘Who do we want to send there?’ What we should do is take a step back and say, ‘Who are the 20 people who are up and coming, talented but not ambassadors yet, whom we want to get a chief of mission office?,’” Burns said. Then plan ahead and decide where each of those officers would go. “Too often, we do it the other way around,” he said.

After he retired from the State Department in 2014, Burns became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and also found time to teach at WIDA. “Training of the next generation of professional diplomats is more important than ever,” he told our students in 2019. “So I hope very much that governments around the world encourage the strengthening of diplomacy, so that we can harness all of that talent.”

As for what’s most important to succeed as a diplomat, he said this: “You have to find wherever the ball is rolling on the field, and with a sense of vision and strategy, move it down the field. While we can’t escape from the nuts and bolts of traditional diplomacy, what’s most important today is getting concrete things done. We need people who are as good at getting things done on the ground overseas as they are in the Situation Room at the White House, driving the policy debate. That’s not a common combination, but it’s what we need to aim for.”

Some of this advice may well apply to intelligence work as well. After all, both diplomats and spies gather information — the difference is that the former do it overtly, while the latter covertly. The other difference is that the CIA is not constrained by the budget limits painfully familiar to the State Department. Just how unconstrained may be surprising even for Burns.

Nicholas Kralev, the executive director of the Washington International Diplomatic Academy, is the author of “America’s Other Army: The U.S. Foreign Service and 21st-Century Diplomacy.”