Ambassador Gina: WIDA Instructor Is First State Dept. Diversity Chief

Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley has never missed a chance to inspire students to pursue diplomacy careers — especially women and minorities.

Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley was a 37-year-old midlevel Foreign Service officer when she arrived at the U.S. Embassy in Israel in 1994, not long after the start of the Oslo peace process between Israelis and Palestinians. Assigned to a position in the political section that required her to become an expert on Gaza, she eagerly began making contacts and following developments in an area considered a high security risk for Americans. But it was the first-ever Palestinian elections in 1996 that tested all her diplomatic skills. In charge of election-monitoring, she put together 10 three-member embassy teams to visit polling stations, conduct exit interviews and report back to Washington.

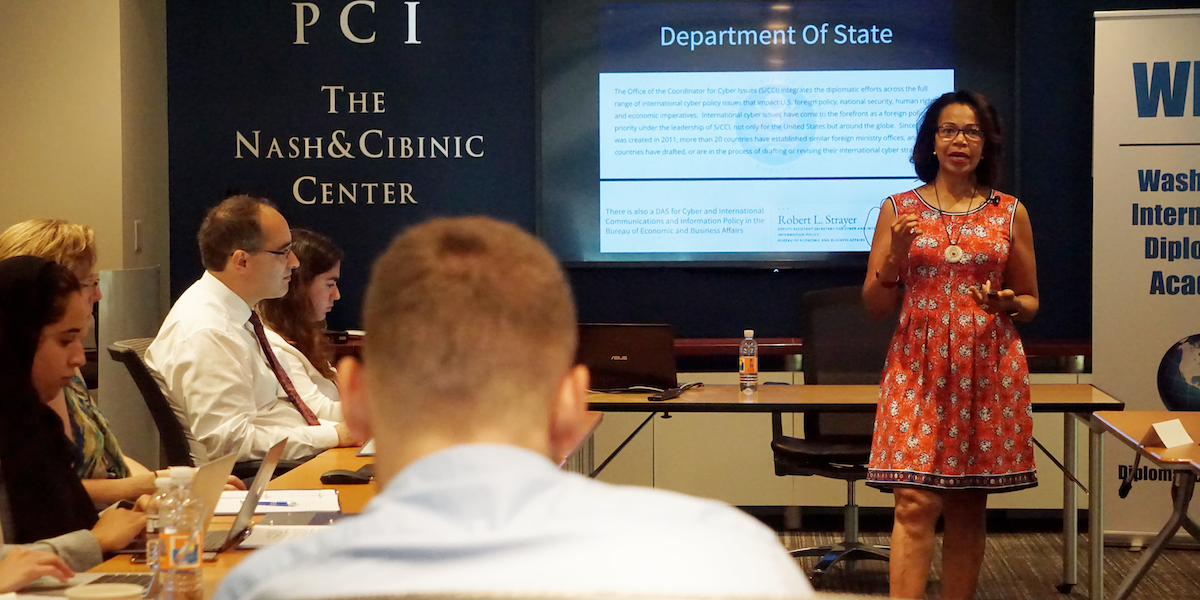

“As I drove around Gaza that day, checking on our teams, comparing notes with other observers who had come in from around the world, I ran into” former President Jimmy Carter, she recalled during a recent course at the Washington International Diplomatic Academy (WIDA), with much of the excitement she experienced 25 years ago. “Preparation, training and tradecraft helped us pull off a challenging assignment and share timely first-hand information with Washington.”

As U.S. ambassador to Malta, Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley took visitors on a rural tour of the country in 2014. Photo courtesy of Merill Eco Tours.

A former ambassador to Malta, Abercrombie-Winstanley quickly became a student favorite when she began teaching at WIDA in 2018. In her sessions in what we call Political Tradecraft, she has been imparting to aspiring diplomats and international affairs professionals the skills that served her well that day in Gaza and throughout her 32-year career — from diplomatic reporting and cultivating relationships to explaining and advocating for specific U.S. policies in other countries. “I’ve been delighted to participate in the training at this academy, because it comprises the sort of training I wish I’d had myself when I joined the Foreign Service,” she said.

Last week, Abercrombie-Winstanley became the State Department’s first chief diversity and inclusion officer. During a formal announcement in the department’s ornate Benjamin Franklin diplomatic reception room, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said she had a track record of “bringing empirical rigor and fierce urgency to the fight for diversity and inclusion, and in pushing for accountability.”

A Black female U.S. diplomat was almost unheard of when Abercrombie-Winstanley joined the Foreign Service in 1985 — the problem is, things haven’t changed significantly to this day. According to a 2018 Government Accountability Office report, women in the service were 35 percent and Black members 7 percent in 2018. But she was determined that her race and gender wouldn’t hold her back.

Her first tour was in Iraq, amid the turmoil of the country’s eight-year war with Iran. When she moved to Indonesia two years later, the nation was still reeling from the aftermath of student protests that had been crushed by the government in the previous decade. The academic community was under surveillance, and student political and social activity was banned. Talking to foreign diplomats, however, wasn’t prohibited, and Abercrombie-Winstanley took full advantage of that opportunity — after all, some of those young people would be local and national leaders one day.

By the time she arrived in Egypt for her third tour, she was used to adapting quickly to new circumstances and jumping into a subject-matter area she knew little about. “I’d been in Cairo only for three days when my boss sent me to figure out why factory workers were protesting in Helwan province. I didn’t even know where Helwan was,” she told WIDA students. No diplomat is expected to know everything, but the good ones figure out how to find experts in a particular area and utilize their knowledge and expertise — and that was what she did.

One of Abercrombie-Winstanley’s most challenging but also most rewarding tours was as consul general in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she arrived months before the 2003 Iraq war started. “We knew the war was coming, and we tried to explain to people what we hoped to accomplish, but we had a very tough time,” she said. “Sometimes you won’t win people over, but you have to help them understand what you are doing and why, and to make sure you keep the lines of communication open.”

When Abercrombie-Winstanley explains diplomatic reporting to WIDA students, they usually ask how it’s different from journalism. “We are all chasing the juicy bits of information, but for different reasons,” she told one class. “Journalists are after a good story that will get them the front page and help them make a name for themselves. For diplomats, it’s not about us — it’s about our government getting the best information as quickly as possible, as well as our analysis, so it can make the best policy decisions. The best value of a diplomat who is a reporting officer is our deep understanding of the host-country and the connections we have. We may not break news, but journalists don’t necessarily stay in the country as long as we do and have the background, context and experience we do.”

Both in diplomacy and journalism, reporting and writing are two different skills, and few people are equally good at both. For Abercrombie-Winstanley, her tour in Israel in the 1990s and the time she spent in Gaza provided some of the best reporting experiences in her career — and she learned a key lesson in writing diplomatic cables. “I remember the first time I wrote a cable at Embassy Tel Aviv,” she said. “I came back from these great meetings in Gaza, my Arabic was flowing, I was really moving — and wrote what I thought was a brilliant cable. But it came back from the political counselor, who was my section chief, with green ink all over it — some people use red ink for corrections, but he used green. He also had a particular editing style. He tightened my prose and moved the most important information upfront.”

Abercrombie-Winstanley has never missed a chance to light a fire in WIDA students’ bellies — especially women and minorities. “We are all here because we share this love of diplomacy,” she told the latest incoming class, “and I hope to give you solid information for starting out and doing well — and to inspire you to pursue this career, because it’s an extraordinary career.”

Nicholas Kralev, the executive director of the Washington International Diplomatic Academy, is the author of “America’s Other Army: The U.S. Foreign Service and 21st-Century Diplomacy.”